On 26 November 2020, the C²DH covidmemory.lu research group held an international workshop attended by experts from European universities who have initiated public COVID-19 platforms to collect testimonies on how the public is experiencing the coronavirus pandemic. In the first part of the workshop, the initiators of the projects in Austria1, France2, Germany3, Luxembourg4, Portugal5 and Switzerland6 shared their experiences and looked back at the history of their platforms. In the second part, the participants discussed some general questions about rapid response collections and, in particular, whether the second wave was already reflected in the submissions.

A Brief Presentation of Various European COVID-19 Collection Projects

Sean Takats (C²DH) started the workshop by reflecting on the origins of covidmemory.lu. Unlike previous rapid response collecting projects he has been involved with (9/11 Digital Archive, Hurricane Digital Memory Bank), the Luxembourg platform on COVID-19 is not about an event that is finished, but rather something that is still unfolding as the collection process takes place. Takats also underlined how these former collecting projects involved an element of technological development and led to the creation of the Omeka S software, which was used by all the platforms presented at the workshop and will, in turn, be further developed as a result. At its inception, covidmemory.lu was not only an opportunity for people to share their experiences, but also a kind of ad hoc response to a most unusual work situation in mid-March 2020: the project helped keep the team motivated during this time.

#vitrinesenconfinement, based at Paris Nanterre University, differs from the other platforms presented at the workshop as it set limits on the types of contributions permitted. Marta Severo recounted how the project, like most others, started as a personal initiative during the lockdown. People were invited to send pictures of windows in public spaces. Intensive use of social media and press communication helped boost the platform’s visibility. The collection has now around 3,000 photos from 1,000 people in 28 countries. Using the Omeka S exhibition tool, the developers plan to ask participants to build their own exhibition with the available dataset. “Tell us your story of the COVID-19 through 10 photos” is an example of how participatory practices with the public can be triggered on collaborative platforms.

In her chronological analysis of the 397 submissions to the Corona-Archiv at the University of Graz, Sandra Hummel revealed some shifts in perception. In the first phase, the collection shows astonishment, fear and insecurity. The second phase is marked by expressions of hope, acceptance and even solidarity. A clear change of attitude or mood was noticeable in the third phase of lockdown, when contributions focused on “the new normal” and pondered the return to normality in daily life. Many people contributed once but some repeatedly uploaded pictures and texts, suggesting that the platform is sometimes used for personal coronavirus crisis management, to communicate worries, express fears to the outside world and gain some sort of psychological relief.

The German coronarchiv.de was “born digital via a Twitter conversation” among various individuals and institutions, as Thorsten Logge recalled in his presentation. It went online on 26 March and today has some 4,500 entries, 3,700 of which have been published. Roughly 1,000 came from a well-established history contest for schools. Like the other initiatives, coronarchiv.de has to deal with copyright issues and the duplication of content. To encourage public participation, crowdsourcing initiatives and oral history interviews with contributors will be launched, and the aim is to find new partnerships with other institutions to stabilise the situation of the platform and broaden the discussion. One future outreach activity is an online teaching course with Indiana University Bloomington.

The Portuguese Memória Covid went online on 13 July after some technical problems, as Helena da Silva explained. Since the summer, submissions from the public have grown to a total of 90, of which 74 are displayed. Like some of the other platforms, Memória Covid uses metadata fields that participants fill out before the stories can be shared. Unfortunately, the geomapping feature is often neglected by users, something that has also been observed for other platforms. As is the case with the other collections, a lot of entries during the first lockdown period can be categorised as artistic works, such as paintings or poems. The small volume of data collected, funding problems and the fact that the project is run by a very small team with limited time have made it difficult to attract new submissions to the website. Such challenges sounded familiar to most participants at the workshop.

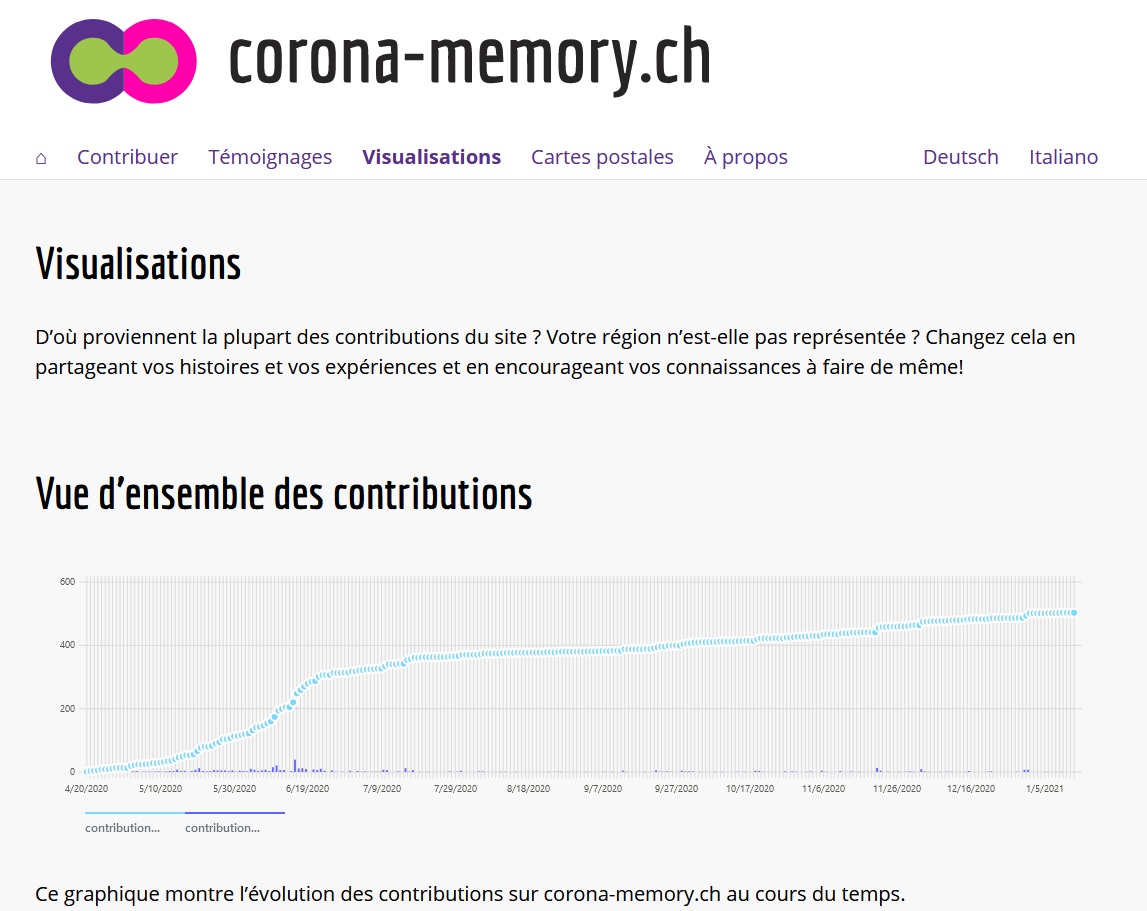

The Swiss portal Corona-memory.ch has published roughly 450 contributions. Unlike other platforms, the entries are checked after publication. A comparison of the languages of the entries shows that the platform reflects the specific linguistic situation in Switzerland. One way used to promote the portal was an initiative which involved the production of postcards featuring content that had been previously uploaded. These were sent to archives, libraries and museums throughout the country. Visitors could write their own experiences on the postcards and send them back. The campaign generated a fair number of new contributions. There is also a plan to hold small-scale workshops with archivists and researchers to raise awareness of the project. However, Tobias Hodel explained that despite the use of social media for promotion, this method had no measurable impact on the size of the collections since the peaks in contributions were mainly achieved through appearances and communication in mass media.

Another way of collecting memories of the pandemic is to harvest tweets, as Frédéric Clavert (C²DH) has been doing. Starting on 15 March, the project has now reached 43 million entries. A challenge is to identify relevant hashtags and eliminate any that are not relevant. The idea is to keep the project going for another 4-5 years. Like all the collection platforms, the project raises issues of representativeness: it is unclear if Twitter is “representative of something else than Twitter”. Initial results show that the second wave was not thematised as frequently as the first. Further analyses can be performed on the data using techniques such as clustering and topic modelling to develop projections over time.

Yet another way to collect memories is represented by the C²DH “Yes we care” oral history project. Benoît Majerus (C²DH) launched the project with a team of ten interviewers at the beginning of April. Short interviews have been and are still being carried out on a regular basis with around twenty interviewees: nurses, physicians, caregivers, hospital cleaners, a retirement home director and even an undertaker. Unlike the conventional oral history approach, which involves carrying out long interviews with people, the idea of the project was instead to conduct short but recurring interviews to create oral history diaries. Although the interviews were carried out less frequently during the summer, 270 interviews representing 100 hours of recording have been conducted so far.

Tizian Zumthurm (C²DH) provided an overview of the entries gathered on the covidmemory.lu platform. Out of 294 contributions, 279 have been published. Most submissions date from spring, and the vast majority are photographs. Many of the entries can surprisingly be classified as quite nuanced and rather positive or neutral in their outlook, which gives us a hint of the audience that is posting. Marco Gabellini (C²DH) started a sub-project on one specific contribution published on covidmemory.lu, namely 110 cartoons drawn by Georg Riesenhuber, an Austrian architect living in Luxembourg. The cartoons represent his experience with the lockdown and the pandemic and comment on social, political, economic and even environmental issues linked to COVID-19. With the help of the artist, he is now recontextualising and categorising the cartoons and their metadata to find patterns and topics.

The Platforms in Context: Representativeness and Resonance

In general, the initiators of the different platforms had expected more submissions to these COVID-19 rapid response collections. In much of the second part of the workshop – an open discussion session –, participants discussed the reasons behind the rather low resonance. One starting point of the conversation was the sobering observation (at least from Luxembourg and Switzerland) that the advertisement campaigns on social media had no measurable effect on the number of entries uploaded to the platforms. Several explanations were put forward. We know that social media is usually consumed passively, even if it is often framed otherwise. Enrico Natale pointed out that the vast majority of work in digital participation projects is normally done by very few individuals. Our platforms want to function differently: they seek different entries from many contributors.

The relatedness of our Omeka S platforms to social media has another effect: much like Facebook or Instagram, the majority of entries present a good or positive image (of oneself). This is not the case with Twitter, as Frédéric Clavert indicated. Preliminary research from France and Italy suggests that more than two thirds of the tweets specifically about the pandemic can be categorised as neutral, followed by negative tweets. Another factor that might partly explain the rather positive outlook of most entries on the platforms is that the majority of contributors seem to have a somewhat privileged background. In spring, there were many entries that depict “bourgeois re-enactments of cultural practices”, as Thorsten Logge put it, such as playing the piano, creating pieces of art, going for a stroll or gardening at home. Contributors thus suggested that the pandemic was a good opportunity for slowing down and finding new pastimes or rediscovering old ones. People that had to continue to go out every day for work probably did not have the same view of the period, and they rarely contributed to the rapid response platforms. As with any historical archive, this representative gap can be partly closed by actively seeking people’s testimonies and/or finding complementary sources, but it remains a serious issue.

Helena da Silva argued that individuals not only think that their experiences or stories are not interesting, but that some may be scared about what might happen to them when they go public. At the same time, contributing can have a therapeutic dimension; it might help people to deal with the difficult situations they are in. These dynamics are certainly worth considering, not only when calling for contributions but also when reflecting on the historian’s role in the collection process.

The initial number of contributions to the platforms decreased as the number of COVID-19 cases began to fall in late spring. Over the summer, the platforms recorded less visitors and items uploaded. When the second wave of the pandemic came in the autumn, most European governments reacted with measures that were less strict than those introduced six months earlier, despite the fact that case numbers, hospitalisations and fatalities in many countries surpassed those recorded in spring. The increase in numbers was not accompanied by an equivalent increase in visitors or contributors to our digital platforms. This might seem surprising at first sight, but the workshop provided some reflections to explain this state of affairs. First, the pandemic had lost its novelty, a phenomenon captured by the widespread idea of a “new normality”. In public and private discourse, many of us, as Marco Gabellini emphasised, have perceived a certain fatigue, even a degree of fatalism. Solidarity with healthcare workers, for example, was more outspoken during the first wave. Individuals applauded on balconies or installed banners, while institutions and companies donated goods. Little of this occurs now. Instead, people are accepting measures such as restrictions on visits to nursing homes, and at the same time we are observing a relativisation or “economisation” of death, as Benoît Majerus pointed out. In public discourse, much more space is now given to the question of how many fatalities from COVID-19 are worth accepting in order to reduce economic losses or minimise restrictions on freedom of movement and assembly. While the participants in the workshop agreed that some very useful insights can be gained in analysing the content of our platforms now, it will probably take more time to fully grasp the implications of these delicate questions related to the consequences of national measures.

Finally, it is important to highlight that the pandemic has unfolded differently in different regions and that people’s experiences have diverged, even though the pandemic was soon labelled “global”. During the first wave, for instance, Italians were afraid to go outside, while the French were not allowed to do so, as Marta Severo explained. During the second wave, Portugal, where restaurants never closed, took very different measures from those taken in France, for example. Such differences draw our attention to transnational developments and questions that are also reflected in the contributions to the rapid response collections. These observations call for a European or even global perspective in framing research questions on the history of the COVID-19 pandemic. For this purpose, a joint collection platform could enable comparison for future historians. However, we should not forget that locality is very important for rapid response collections. If collecting institutions are well grounded in local communities, it is easier to find contributors and convince them that their stories are relevant and interesting.

- 1. Sandra Hummel (Universität Graz): https://corona-archiv.uni-graz.at

- 2. Marta Severo (Dicen-IDF/Université Paris Nanterre): https://vitrinesenconfinement.gogocarto.fr

- 3. Thorsten Logge (Universität Hamburg): https://coronarchiv.de

- 4. Christoph Brühl, Marco Gabellini, Stefan Krebs, Sean Takats and Tizian Zumthurm: https://covidmemory.lu; Frédéric Clavert: https://www.c2dh.uni.lu/fr/thinkering/traces-et-memoires-en-devenir-dune-pandemie; Benoît Majerus: https://www.c2dh.uni.lu/fr/thinkering/traces-et-memoires-en-devenir-dune-pandemie-2-yes-we-care

- 5. Helena da Silva (Universidade Nova de Lisboa): https://projetos.dhlab.fcsh.unl.pt/s/memoriacovid

- 6. Tobias Hodel (Universität Bern), Enrico Natale (infoclio.ch): https://www.corona-memory.ch