We drew inspiration from various sources in the development of the course structure. As a first of its kind, interdisciplinarity was key. Incorporating research from museum studies, user experience (UX) design, digital history, and computer science, we set out to bring together salient theoretical concepts from different disciplines and ground them within a series of applied projects throughout the semester. We borrowed from museum studies curricula, including a course by Katherine Burton Jones at Harvard University, as well as a number of multimedia sources such as Netflix documentaries, TED talks, and podcasts.

In an effort to continue the conversation beyond the classroom, we adopted the digital annotation tool hypothes.is, which allowed students to engage readings collaboratively in preparation for in-class discussion.1 After each session, two or three students posed additional questions to continue the discussion on the class forum. We adapted the course format slightly after the unexpected lockdown and consecutive move to remote teaching as explained in another blogpost. Weekly readings and discussion sessions culminated in a short essay where students evaluated a digital collection of their choosing. For the final project, students teamed up to create their own online collection and launch a curated exhibit via social media.

- 1. For more detail on the use of hypothes.is see Van Herck, Sytze and Morse, Christopher. "The Recurated Museum." Digital History and Hermeneutics. 6 June 2020. http://dhh.uni.lu/recurated-museum.

The Role of the (Virtual) Museum

Early in the course we discussed the evolving identities and roles of museums. For example, we asked the students to consider what kinds of institutions counted as museums (The Recurated Museum: I. Museums as Producers of Meaning, slides 13-20). While there is indeed some consensus over what museums are or should be, we highlighted the challenges surrounding their precise definition. Museums are cultural institutions, legal entities, educational experiences, community venues, and even spaces of play or calm respite, among many other things. Recent controversy over a new definition suggested by the International Council of Museums (ICOM) reiterates this exact tension. The evolving identity of museums has major implications for museum staff who frequently take on new responsibilities as a result. We considered the role of the curator, for example, noting that their work is not always transparent (The Recurated Museum: I. Museums as Producers of Meaning, slides 21-29).

Curation takes on new dimensions in digital spaces, where cultural professionals increasingly collaborate with designers and developers to create interactive exhibits and virtual tours. In addition to their on-site visitors, it is increasingly clear that museums must also cultivate digital communities.

We then considered the increasing necessity for museums to cultivate digital communities. This coincides with the massive influx of visitors to museum websites each year. In the case of the Louvre, their website had 16.1 million visitors in 2015 alone, many of whom were digital-only visitors due to distance, preference, or other circumstances.1

- 1. Evrard, Y., & Krebs, A. (2018). The authenticity of the museum experience in the digital age: The case of the Louvre. Journal of Cultural Economics, 42(3), 353–363. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10824-017-9309-x

Our course discussed how the internet has affected community engagement and how online content creation changed museum practices. We prompted the discussion with a short fragment from #cats_the_mewvie (36:02-41:16) and later discussed online community engagement in more detail with Wouter van der Horst, one of our guest lecturers.1 Based on an exercise from the Incluseum, we turned our attention to diversity and inclusion (or lack thereof) in museums, an issue which the students continued into the forum discussion.2 Furthermore, students commented on Nina Simon’s TEDx Talk on The Art of Relevance which describes the financial struggles and initial lack of relevance to the community of the Museum of Art History in Santa Cruz.3 Simon argues that museums can create meaning and lower effort for people unaffiliated with the museum community to visit by cultivating relevance. For example, she discusses an event called F* my ex, where visitors collected items that reminded them of their exes on Valentine's Day. In another example, she describes an institution that worked together with local indigineous leaders to redesign its spaces with elements relevant to the local community, such as the inclusion of a firepit for music, dance, and storytelling. From there we introduced user experience (UX) design methods and their application in museum contexts (The Recurated Museum: VII. Museum Exhibition Design through UX, slides 10-41, 45-54).

- 1. Margolis, Michael, dir. #cats_the_mewvie. Good Human Productions. 2020. https://www.netflix.com/lu-en/title/81218137.

- 2. Moore, Porchia. "Who Is Your Museum For? A Tool for Initiating Critical Conversations and Reflection." The Incluseum. May 2015. https://incluseum.files.wordpress.com/2015/05/who-is-your-museum-for.pdf.

- 3. Simon, Nina. "The Art of Relevance." Filmed 4 May 2017 in Palo Alto, California. TEDx video, 12:28. https://youtu.be/NTih-l739w4.

What constitutes a virtual museum? Although our discussion was by no means exhaustive, we identified several common ideas (The Recurated Museum: III. Digital Collections, Exhibits, & Education, slides 11-22). Virtual museums may evolve around object-centered exhibitions, or collections based on particular thematic areas. Examples include personalized or socially-oriented digital experiences, 3D reconstructions of historic objects and places, and even traditional museum websites. We also discussed the role of museum educators and how they can cater to different learning styles (The Recurated Museum: III. Digital Collections, Exhibits, & Education, slides 26-36).

Museums specialize in designing engaging exhibitions through scenography and interactivity, which we translated into our course's digital collection by considering different approaches to engaging visitors. We designed stories that highlighted the exhibition without relying solely on the novelty of technology, balanced the tension between richness of information and brevity (e.g. short but educational YouTube videos), and considered visitor engagement through participatory means (e.g. Twitter polls) and through storytelling (e.g. Instagram stories).

Evaluating Online Collections

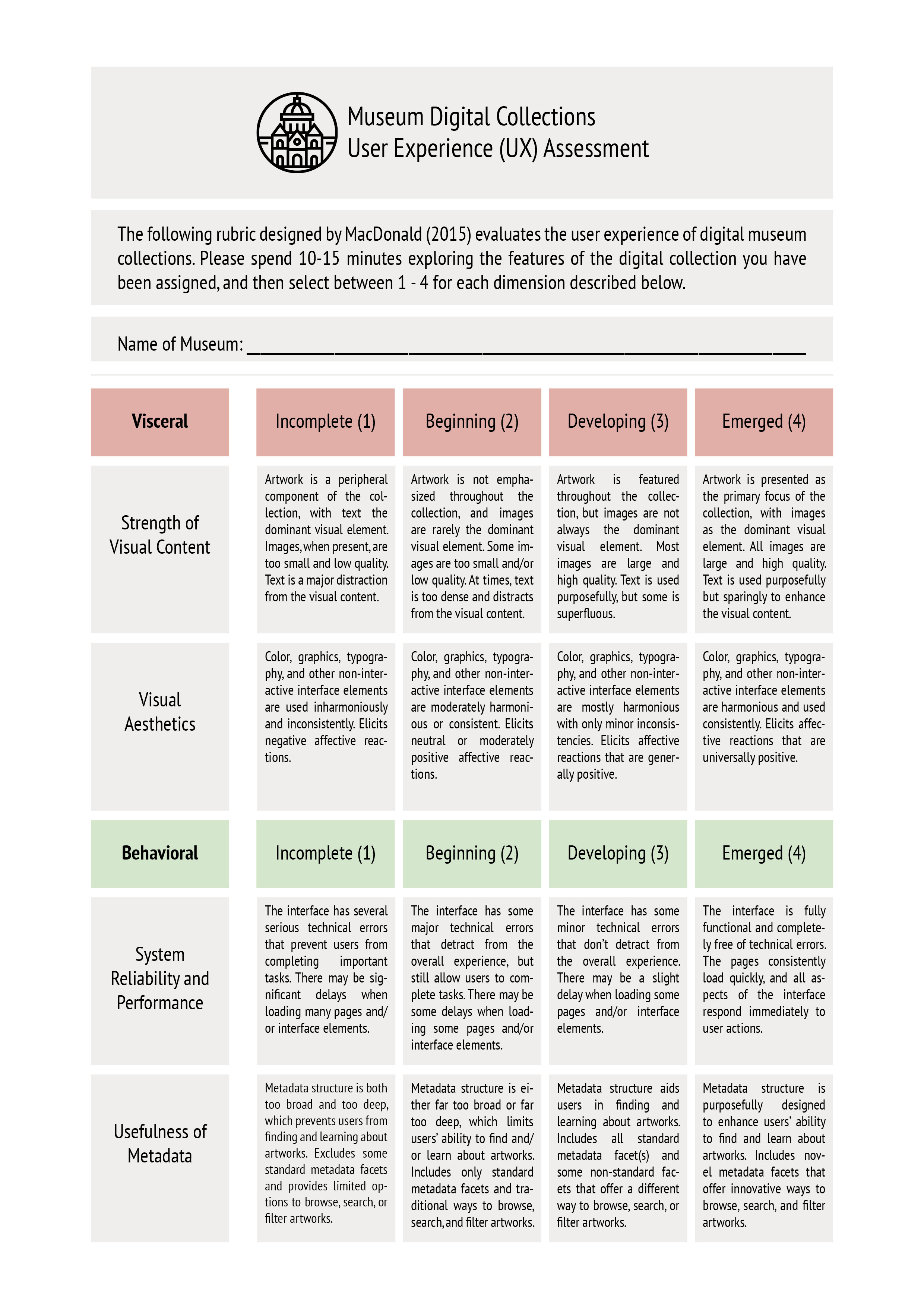

Museums all around the world have adopted digital platforms of varying levels of sophistication to share their collections online, but how might we critically analyse these platforms? As digital collections and other types of virtual museums increasingly become the norm, cultural professionals must carefully consider their design and implementation.

There is a small but growing collection of tools available for the evaluation of digital collections, and for the purposes of our course we introduced a rubric created by Craig MacDonald.1 Based on Don Norman’s seminal work Emotional Design, MacDonald constructed his rubric to assess the user experience of a digital collection across three emotional design categories: visceral, behavioral, and reflective design.2 In order to make the rubric more accessible, we designed a worksheet with each category of experience and the respective scoring rubric.

We instructed students to evaluate different kinds of digital collections throughout the semester using the MacDonald rubric. This culminated in a short essay assignment where we asked students to reflect on a digital collection of their choice through the lens of the rubric, and then to carefully critique the rubric itself to better understand its strengths and limitations as an evaluation method.

- 1. MacDonald, C. 2015. "Assessing the user experience (US) of online museum collections: Perspectives from design and museum professionals." Paper presented at MW2015: Museums and the Web, Chicago, IL, USA, April 8-11, 2015. https://mw2015.museumsandtheweb.com/paper/assessing-the-user-experience-...

- 2. Norman, D. 2004. "Emotional Design: Why We Love (Or Hate) Everyday Things." https://www.nngroup.com/books/emotional-design/

The Experts

First, Blandine Landau at the C²DH acted as an expert advisor. Her depth of experience as a museum curator helped to ground the theoretical work we discussed in class in the day-to-day realities of the museum. Moreover, she gave a fascinating guest lecture on the evolving role of curators, and how cultural professionals influence the type of discourse museum objects convey. We also thank her for her feedback on the development of the digital exhibition.

Jeff Steward, Director of Digital Infrastructure and Emerging Technology at the Harvard Art Museums, joined us mid-semester to discuss the role of museums as centers for research and teaching. He also shared the ways in which he and his team augment their digital collections through smart tagging, feature detection, sentiment analysis, and various kinds of interactivity. Finally, he introduced the Harvard Art Museums API which is accessible to the public, allowing them to engage the collections programmatically and to create their own digital experiences.

Finally, our third guest speaker was media guru Wouter van der Horst, founder of We Share Culture and former Digital Learning Educator for the Rijksmuseum. He demonstrated the ways in which the boundaries between offline and online are fading for museums, and offered a new definition for museums as an entity that facilitates meaningful interactions between collections, narrative, and humanity. As a museum experience designer, he emphasized the role of social media platforms on the success of museum digital outreach.

#LuxLife

Due to the COVID-19 outbreak many museums closed their doors to the public, and as a result we had to reconceptualise the final assignment on short notice. Originally we planned for a presentation of the online collection in the Lëtzebuerg City Museum MuseTech lounge, but in lieu of a physical space, we prioritised the social media campaign element of the exhibition. In many ways this was a blessing in disguise because the final format closely aligned with the trends that Wouter van der Horst highlighted in his guest lecture.

An important objective of the exhibition was to carefully consider its design through the lens of visitor experience. First we looked at other museum channels on YouTube, Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram (The Recurated Museum: VI. Brainstorming Session, slides 11-13) for inspiration, keeping in mind the Lëtzebuerg City Museum’s mission statement. The museum mission relates directly to Luxembourgish identity and informed the exhibition’s joint purpose of unifying natives, immigrants, and cross-border workers in their connection with Luxembourg.

We adopted methods from UX design (word association, “how might we...”) to brainstorm about different themes for the exhibition. We settled on local production, art & photography, and two types of Luxembourgish cuisine: Gromperekichelcher and Kniddlen. Students conducted user studies through surveys and (digital) museum observations, leading to the creation of visitor profiles (personas) to help inform their social media strategies. Next, each group created a mock-up of their social media profile with a banner image, profile image, exhibition description, list of relevant hashtags, and examples of posts or a storyboard for videos (The Recurated Museum: VI. Brainstorming Session, slide 19). We then synthesised the findings from students into a joint social media strategy. Based on our guidelines, each group then created a YouTube video, an Instagram story, as well as a few Instagram and Facebook posts, and a short Twitter thread to promote their group’s exhibition. Finally, each group was in charge of managing a single social media platform for the course, publishing posts and replying to comments if needed.

We worked together with Luke Hollis of Archimedes Digital, creators of the Orpheus platform, to create a unique digital presence for the collection. Students collected copyright-free content, created their own images, and contacted local artists for permission to exhibit their work. They provided the necessary metadata and wrote short stories connecting the various artefacts to create different narratives about life in Luxembourg. The cross-platform exhibition is available on YouTube, Instagram, Twitter, and Facebook. The digital exhibition can be found on luxlife.orphe.us.

Museums At Home

As museums were forced to temporarily close their doors as a result of COVID-19, we witnessed as a class the sudden shift in priorities towards creating digital cultural experiences at institutions all around the world. Hashtags celebrating cultural participation at home such as #MuseumAtHome and #CultureChezNous went viral. The #GettyMuseumChallenge, in which people recreated artwork using only objects found around the house, provided much needed levity during an otherwise difficult time.

Additionally, virtual tours began popping up across social media, eventually growing into consolidated lists on Twitter, Facebook, and other platforms.1 We had a look at some of these tours and asked students to critique them based on concepts discussed in class. Museum professionals began appearing on social media outlets to give short interviews, highlight parts of the collection, or even lead tours of their own. UNESCO, ICOM, and various other cultural heritage organisations hosted recurring talks and town hall meetings to discuss the effects of the virus on artists, cultural professionals, and institutions alike.2

Even now at the time of writing, many of these challenges still remain and will continue to influence the cultural sector for years to come. In spite of the sudden (and in many ways unexpected) necessity for comprehensive digital strategies for museums, we do not believe that the digital experience of a museum can replace an in-person visit, nor do we believe that this should be the goal of any digital strategy in the first place. Instead, cultural professionals must take advantage of what digital spaces allow visitors to do that physical spaces do not.

- 1. Some examples: 1) 10 Best Virtual Museum Tours, 2) Coronavirus - Covid-19: museums around the world offer virtual visits

- 2. For example see a recent meeting by UNESCO or a recent ICOM webinar about reopening after the pandemic.

Note:

We have made our course slides available on SlideShare to anyone who may find them useful (CC Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike License). We hope these resources can support your teaching or research.