As part of the Popkult60 project, there have been many surprising discoveries of the media of the 1960s. When we discovered the Feu de Camp du Dimanche Matin radio recordings in 2019, we knew we had found a unique media crossover and were keen to further explore the links between our fields. Le Feu de Camp (Sunday morning campfire) was a radio show presented by creators from Pilote and broadcast on French-speaking commercial station Europe n°1 from October 1969, lasting for 13 episodes. It was also advertised in Pilote, with adverts appearing in 10 issues in 1969 that coincided with the episodes. The show stood out as it aimed to transpose the spirit - stories, celebrities and general attitudes - of the irreverent magazine into radio, going against the long-held tradition of directly adapting comics stories into audio dramatisations.

Our research journey into the show began with Richard’s trip to Europe n°1 where an archivist asked if he also wanted to listen to something they had found but that ‘probably wouldn’t be anything of interest.’ Upon listening to the one surviving episode at the archive, he realized that it was a show by the team from Pilote, and hastened to bring it Jess’ attention. It seemed completely logical to combine forces to work on it together. We didn’t think at that time just how much we would be able to discover! We soon understood that radio and comics enjoyed a long history of crossover with popular adaptations of comics stories like Tintin or Superman appearing from the 1930s, and countless other examples. The birth of Pilote in 1959 also had strong ties to radio as it had been partly financed by Radio Luxembourg with two of its DJs on the editorial committee, before the magazine was bought by publisher Dargaud in 1960. Feu de Camp meanwhile was different, because it tried to make a new form of radio rather than a simple adaptation.

At first, we wanted to work on an article (hopefully to be published soon). This work allowed us to tackle the theoretical basis of the crossover and developed several concepts relating to the show including its playfulness, its chaos and its attempts to bridge the gaps between the two media. In the article we discussed the elements within the show and concluded that their reliance on the use of imagery often did not translate well to the show and added to the chaotic atmosphere. Some examples include when a guest (usually another artist from Pilote), the team would forget to announce them for listeners, or when highly visual jokes such as a fire-breathing trick gone wrong would have to be described in lengthy detail to explain what happened for the listener.

It did not feel like a traditional academic article could fully capture the essence of the spirit behind this research, however. The radio show proclaimed itself to be ‘the most visual radio show’ and we wanted to bring to life some of the imagery by using a parody of our real research experiences. The process of research is one that is almost never shown, so we also really wanted to highlight our work process and the act of working collaboratively. To do so took a great deal of thinkering on how to transpose the audio inspiration of the show back into the visual. Thanks to the Thinkering Grant, we were able to experiment with both the visual and the audio in a reimagining of what the media crossover means to us and our work. We took our main inspiration from one aspect of the show that we felt worked the best in the visual-audial transfer, Bougret et Charolles, a sketch about a police detective who solves cases using ridiculous logic. Bougret et Charolles was subsequently also made into a comic strip in Pilote, thereby completing the media cycle loop. In our comic, we used parodies of those characters and ourselves to make Burtgrey & Richerolles.

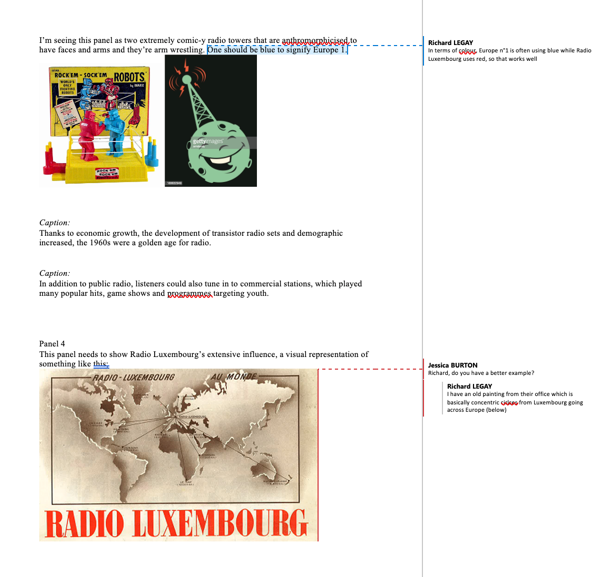

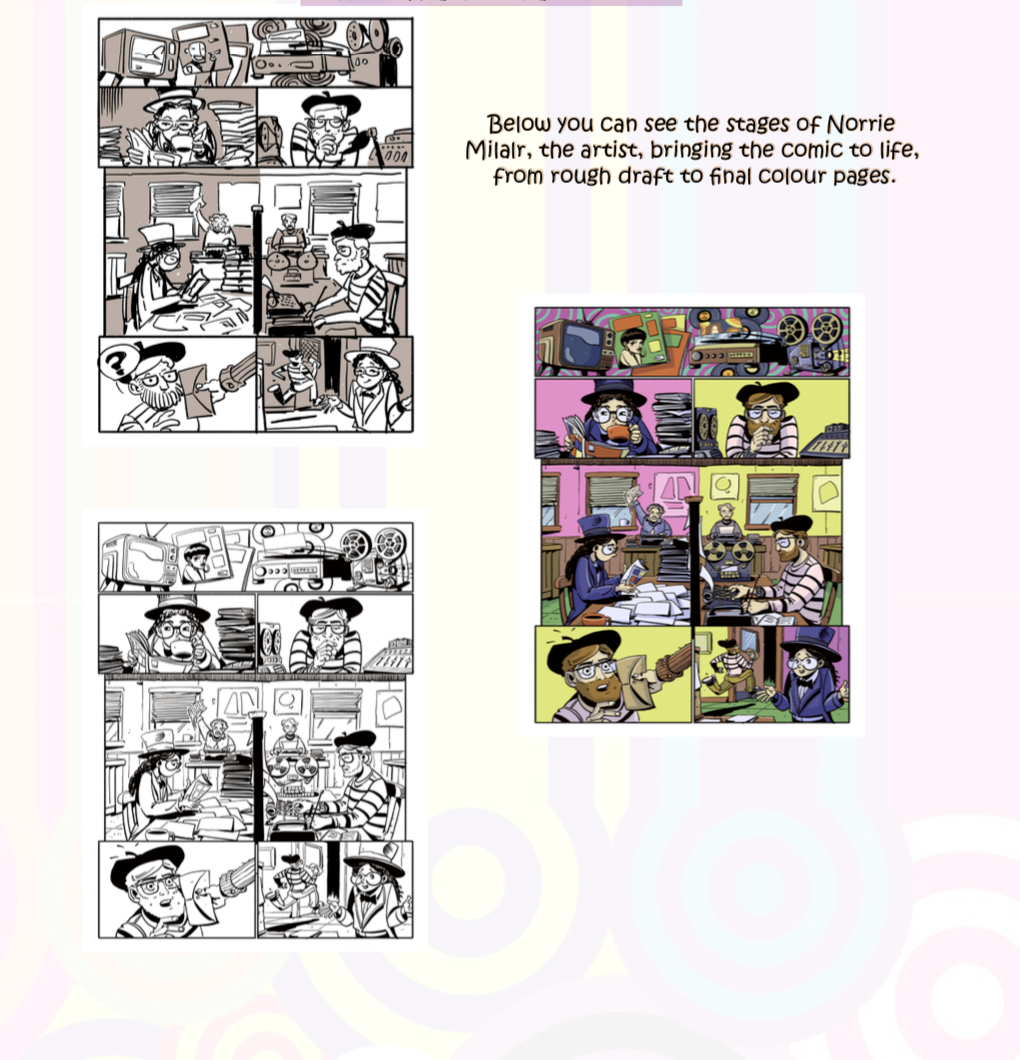

The end product is a great demonstration of what media scholars can do when they combine forces. Though we are extremely proud of the results, we cannot underestimate the importance of the process of its creation. First we had to learn to work with each other’s media and move out of the comfort zones of our own fields. Jess for instance had never known how to analyse a radio piece, but this was the crucial stepping stone in understanding the show, so we began by listening to the episodes several times over together before then transcribing it in order to make an analysis of what we could hear. While Richard had always been a keen reader of BDs, he knew very little about the ways to actually make one. He is now more aware of the work and level of details behind each choice of image, which will most likely influence his work in the future. It was also important to trust our artist, Norrie Millar, as much as possible. In the script for the comic, we provided as many images as possible to show what we had in mind and give visual references for the artist to work with. We also gave him a transcript of the show, with some of the main sketches highlighted. He did an amazing job and often beyond what we expected. Below you can see some screenshots of our script, and the process pages of the artwork.

Download the comic strip in

|