Oftentimes, when I mention that I study Digital History to people that are not working on it, I get questions on some computer tricks. Everybody wants to make things faster and easier, and there is an assumption that digital tools can bring (or should bring) a solution for almost everything. Doesn’t matter if the subject of study is “digital related” or not, if tools cannot solve problems, it can be misunderstood as if those “digital fancy things” are not really great for nothing in humanities/history realm. And, suddenly, these people interest seems to disappear. “If it has no utility, then we don’t need it”, at least, in the immediatist point of view.

However, there are a bunch of tools that can help historians in their daily work. Of course, I don’t know all of them, and that’s why, many times, I feel unprepared to answer this kind of question. Anyway, before searching for a tool, one needs to know for what purpose she or he needs a tool.

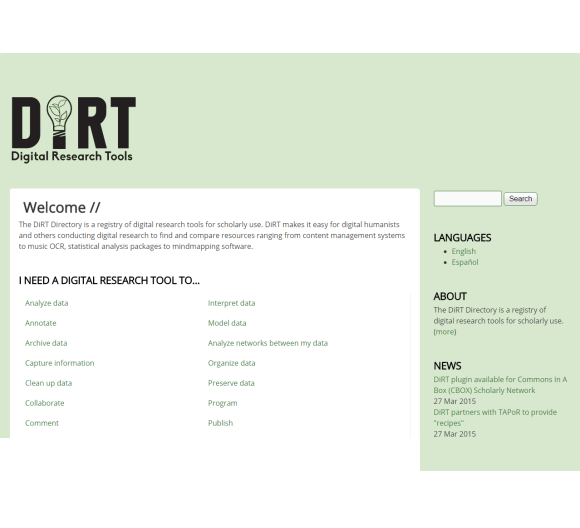

Cleaning my Favorites bookmarks, the other day, I came across a link of the American Historical Association with useful references for Getting Started in Digital History. Among literature and projects, I found (again) this directory of tools:

If you are not familiarized with what can be done with tools and if you don’t really know the needings of your own research, it might be not so useful, but you can always jump on it, look for some reviews on specific tools you like, search for online tutorials and play with it.

It doesn’t mean that one needs to believe in some sort of technological solutionism, as criticized by Evgeny Morozov, and lose his/her time surfing the web endlessly, looking for the perfect tool, or trying to learn how to use it only for the sake of using it, because it’s hype. I believe it’s more about seeing the meaningful connections between the human and the machine work in one research, and try to figure out which kind of questions can be answered with this hybrid conjunction, mankind and computers, tradition and new technologies… Perhaps, it can turn out not only that is possible to answer X or Y question in a different way, favoring new approaches, but also be insightful for the proposition of new questions.

It’s is not a matter of changing the whole tool box of historians for a very new brand digital thing. But how to associate what we already know from our craft to the assistance those digital things can give to us.

One important exercise, is trying to not create a natural opposition between (digital) technologies and the humanists (and historians) work. Federica Frabetti has discussed the resonances of such complicated assumption in DH in her Rethinking the Digital Humanities in the Context of Originary Technicity (2011). After showing that the utilitarian mode of technology has been dominating the Western thoughts for almost three thousand years, as an Aristotelian heritage, according to Timothy Clark, she did a strong call for critical thinking on it. She emphasized the needing for questioning “the model(s) of rationality on which digital technologies are based” while importing it to digital humanities. Such reflection on the digitality, which I very much like, could hopefully show that technology and humanities are not separated, or opposed. Rather, they can be (are) complementary. Frabetti developed an interesting argument on it, bringing together different philosophical views on technicity/technology and knowledge. In dialogue with Derrida, she argues that “dissociation between thought and technology is – as is every other binary opposition – hierarchical, since it implies the devaluation of one of the two terms of the binary”.

A second good exercise is forgetting about that perfect tool. In another opportunity, Max Kemman wrote that “no tool can do all research for you” (2015), collecting his notes from the second edition of DHBenelux conference, last year, in Antwerp, Belgium. His impression on that conference echoes my perception on the Trier Digital Humanities Autumn School 2015, co-hosted by Trier University and the University of Luxembourg. Concernings on tools were almost omnipresent in the lectures during that week, starting with the first speaker:

Do not use a tool, which do not understand. Manfred Thaller #DH Trier

Thaller’s warning is a great north. However, a relative ignorance can make people be afraid of trying. As Andreas Fickers pointed out we need to be playful with those tools, use the digital without fear of taking risks, because research is about taking risks. As Claudine Moulin said in her opening words of this Autumn School the time for testing has come, but bear in mind Thaller’s reminder. You don’t need to avoid the tools because you don’t know them, dedicate yourself to understand it and learn something. If at the end of the day you do not find that it was useful to you, some knowledge will remain out of your tests. Maybe, that is not the right tool; maybe you will need to search for another one, or just other(s) to combine. Tools can also be complementary among them. You just need to understand what you need and try to find which (one, two or more) work better for your case.

As Kemman also noticed in the same blog post: “While DH loves to develop tools, tools do not always reach their potential adoption by the target audience”. Apropos, Kemman and Martijn Kleppe presentation on user research in digital humanities (and its value for developing tools) at Benelux 2015, showed that “due to the many unique and out-of-scope user requirements, […] there is a tension between the specificity of scholarly research methods, and generalizability for a broader applicable tool.”.

Moral of the history? First, know your needings and, if you do not know a tool, don’t be afraid to try it, one or more of them. Study it, learn about it, play with it. And, if you do not like it, or if you like but think it could work differently, search for alternatives. But, most important: share your experiences with other colleagues and, if possible, do write a review on the tools you have used. It must be useful for others like you and also for those who work developing it.

But critically. And be happy!

I hope the Digital Research Tool will be of help for some.