Note: This blogpost is a summary of the full article. For the detailed explanations and all the screenshots, please open the full article in PDF.

A Nodegoat Odyssey

Working in Nodegoat requires the development of a data model, which is composed of two main elements: types and classifications. I developed my data model based on the diary of British WWI soldier Sidney Bland, who served in the Welsh Guards. I wanted, in a first step, to retrace his movements on a map, and, in a second phase, to visualise the types of events and actions that happened on the different places he has been to. My idea was to link all this together on one single map, and to see whether I could get new insights (besides tinkering with Nodegoat). Whereas actions were defined as being carried out directly by Bland (taking a bath, for instance), events happened without his direct involvement or influence (such as artillery bombardments).

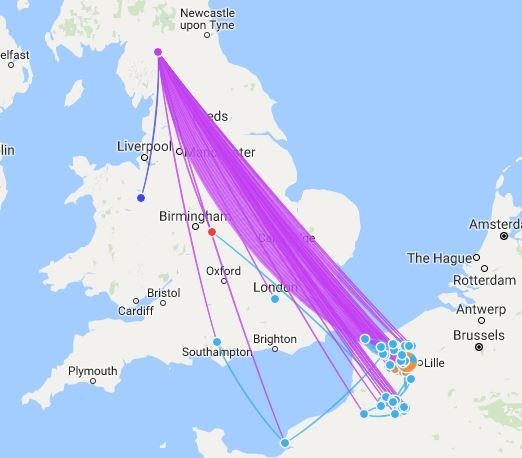

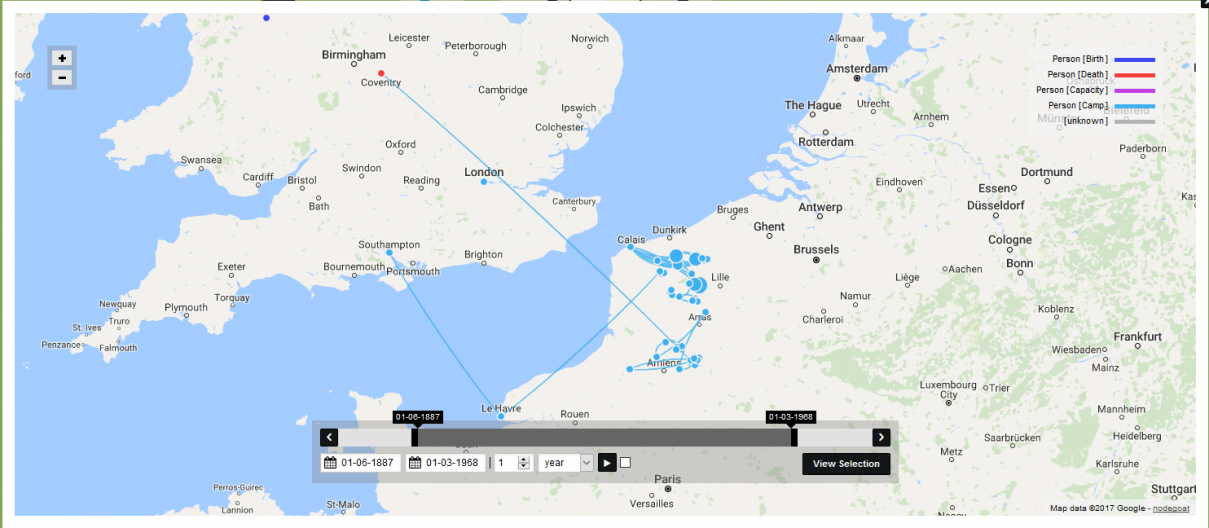

Nodegoat was developed for bringing together a considerable amount of data, and not for one single source, even less a diary. This was one of the main causes of many problems I encountered while working with the software. Every time Bland left a town on the same day he arrived in, lines between two stops were not drawn. Yet, the software created a connection between the last place in the diary and his place of death, though many decades lie in between. In this case, the problem could be solved by removing information related to Bland’s death from the map filter or deleting it altogether. For the missing connections, a workaround solved the issue, but only before I entered all the information related to events and actions in the second phase. Since then, it hasn’t worked anymore, for a reason unknown to me.

Some of my work proved, in the end, to be a loss of time. The fact that I had never worked with Nodegoat before, and thus lacked the necessary competence, was one important reason. Though I defined a specific type for events in Nodegoat and entered a series of events, they could not be shown on the same map than Bland’s movements and actions, but only separately. I also distinguished between different labels to categorize the actions and events, such as “Entertainment & activities” or “Frontline”, but I was not able to assign a colour to each label (nor did I find such an option). As a consequence, and to put it bluntly, it was not possible to see the difference between carrying out an attack and eating pudding.

In hindsight, I chose a very bad example of a source for Nodegoat. Not always did Bland indicate precise locations, and therefore, I had to leave out some stops for a better visualisation. I also relied on guesswork and logical deductions because of abbreviations or wrong spellings of town names (instead of “Le Havre” he wrote “La Harve”, for instance). Moreover, Bland made no statement on the distance traveled when he marched from a camp to the frontline. In many cases, I had to use approximations and assume that he stayed in the same area of the most recent town specified. The same was true for some of the events he describes in his diary, such as bombardments, which can generally be heard from many kilometers away, and where I used his own location as reference.

The lessons to be learned: reflections on the use of digital tools

After all this work, the question I had to ask myself was whether Nodegoat could provide me with new insights on Bland’s activities between August 1915 and December 1916. The short answer is no. Though the map allows an appealing (albeit problematic) visual overview of Bland’s journey, I did not gain new information. The number of lines between two places showed how many times he travelled back and forth, but I would also learn this by analysing excel tables. Furthermore, how many lines might be lacking just because of the problems I have encountered? Indeed, Nodegoat is not designed for using one single diary, but for bringing together large amounts of data with a specific research question in mind. The sources, however, need to be reliable and precise. In my case, I had to make too much compromises for the sake of simplification and better visualization. As the one responsible for creating the database, I knew which workarounds I used and what had to be left out, but what about the public? What about those people who look at the visualisation and believe the information to be reliable and accurate? How would they interpret the missing links and the redundant lines?

The aim of my account was not to give useful instructions on working with diaries or offer a manual for using Nodegoat, but the main purpose consisted in illustrating that the use of digital tools needs to be critically engaged. Mistakes are part of the process. Digital humanities are as much a great opportunity for new approaches as an art of failure and critical reflection. Nodegoat draws its strength from the quantitative analysis. The results of my analysis would certainly be more meaningful if I had used more diaries and added more data. In addition, I had no previous knowledge of the program, and therefore fostered wrong expectations towards its possibilities, resulting in a loss of time for ideas that would not work. The efforts I invested in creating a database of Sydney Bland’s actions with the aim to visualise on the map the different types were in vain for the purpose I had in mind.

However, these failures and issues have taught me many important lessons on a methodological level. Digital tools such as Nodegoat have their limits. It is possible to see the intensity of a phenomenon, but not necessarily the exact nature of it. On the map, it looked like Bland was staying in the same town until he left, but no distinction is made between frontline and staying in reserve, except for the labels I used which were not visualised. Bland understandably did not indicate precise coordinates of the trench he was holed up in; and why should he even specify it in a diary? In addition, the map I created showed that between some stops, Bland travelled more than between others, but by what means, in what conditions and for how long remain unknown.

Thus, when it comes to using digital tools, it is necessary to reflect on the type of sources used. A program is only as good as the data – and the user. The engagement with digital tools requires critical reflections on their purpose. What do we want to analyse? Can such tools help us in better understanding a phenomenon? Are our sources appropriate? Is our data precise enough? Should we even use a program for the sake of visualisation when so many compromises need to be made? With all the approximations and workarounds, I was not doing the work of a historian. In fact, I bended my data so it could fit the program’s capabilities. A tool, however, has to be adapted to our needs, not the other way around. If not, the same will happen as in my case: missing links, wrong visualisations and a certain degree of frustration. In this case, it would be better to abandon it, and look for an alternative.

My experience with Nodegoat illustrates the confrontation with a black box. I do not know the software code, and thus cannot fully grasp the data processing, especially when its results turn out to be different from my expectations, or simply wrong. I use its interface and enter data, and the results are shown in beautiful graphs or erroneous representations. But what happened in between? Solving problems such as missing links or needless connections requires knowledge of the ‘inner life’ of the program, a basic understanding of its possibilities and limits. Yet, choosing the right tool would also avoid having these problems in the first place. This is where digital humanities are so important: their aim is not only to show how useful digital tools can be, but also to provoke critical reflections on why things can go wrong and what really happens behind the interface. In our world, we take technology for granted, seldom think about its implications and rarely engage with its functioning. I encountered many problems when working with Nodegoat, but they helped in revising my own naiveté and taking a more critical stance towards digital tools. I certainly do not want to claim that digital tools are useless. On the contrary, but they only unfold their full potential when we really know how to work with them, and when to use them. As Mervin Kranzberg once wrote, “technology is neither good, nor bad; nor is it neutral”. To which I would add that we only need a critical mindset.