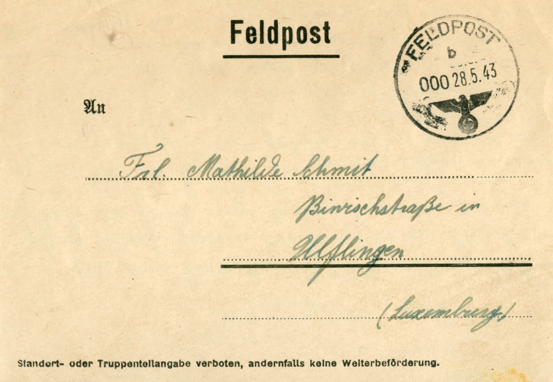

The conscription of young Luxembourgers is mostly recorded in official documents, including police files, enrolment registration records from regional authorities, transportation lists, and military records about their service. However, for the study of biographies a more personal window into the lives of the affected people is required, as behind these administrative files lay 10.000 life stories.

Project Warlux

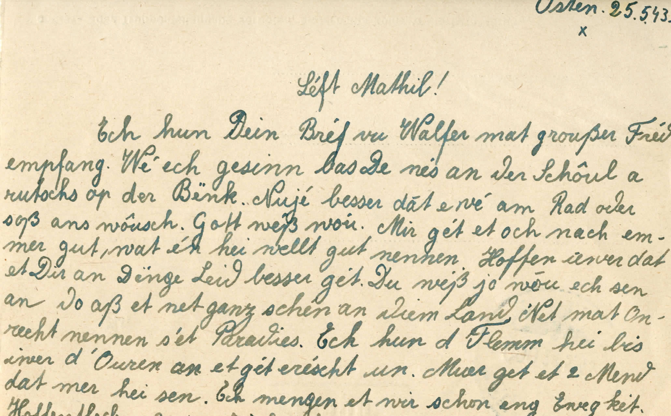

The focus of WARLUX is to analyse the evolution of experiences evoked by World War II from an actor-centred perspective and to re-evaluate the traditional categories of analysis by taking into account the multitude of war experiences and coping strategies of the people affected. This biographical focus will help to illuminate the individual experiences of soldiers, recruits, and women. In this regard, personal documents will constitute the core source for the overarching research question, including enlistment records, personal files of the German armed forces and the RAD, and ego-documents such as letters, diaries and autobiographies. Nevertheless, the project aims to collect the personal insights, voices, and subjective impressions of the affected people. How is it possible to gain insight into the personal and individual views of our objects of study? Their names are mostly known in memorials, lists and literature. Between year numbers and historical frameworks, biographies consist of much more, such as individual preferences, backgrounds, dislikes, characteristics, relationships to friends and family, etc. This is not readable from official documents and from lists and passports from the military service. To analyse their views, we need to dive deeper. What is left of their voices? Next to memoirs and oral history videos there are more sources to consider, the so-called “ego-documents” such as diaries and letters. Letters are a unique source and provide more information about individual fates than administrational documents.

If the letters are preserved they can provide insight into the stories of the affected people. The war was a major event for everyone in Luxembourg. This crucial epoch changed the lives of the entire country and robbed its citizens of their hopes and dreams. The letters and other ego- documents represent a slice of their fates, written from distant places, far away from home and loved ones, desperate, sad and scared.

What can these letters tell us, from an analytical and scientific point of view?

Families and friends were separated. The connection to home was only possible via letters and parcels, a communication network distributing news and greetings and signs of life. Nevertheless, the experiences distinguish themselves from each other in a crucial way. While the families at home had to think about food, logistics, and Nazi terror and switched into survival mode, the young men and women abroad suffered from homesickness and fear and the hope for the war’s end. The letters represented a bridge to the homeland.

War letters and ego-documents in historical research

The analysis of letters is different than memoirs or administrative documents. Letters express the momentum of the experience of the event, emotions and thoughts. Memoirs written years or decades after the war can represent a distorted image of the true events but letters can show only a short glimpse in everyday life. One must also note that the content and the style of the document vary by its intended audience. A mother received a sign of life from her son (everything alright, I have enough to eat and I am doing fine), while letters addressed to a friend might include other storytelling about front life. It should be taken into consideration which information the writers wanted to tell the others – what was essential to them and what the other needs to know.

The war letters were written under abnormal conditions. Some things remained unspoken; some senders incidentally integrated the horror of everyday war life into their letters only as a secondary matter. The reality of war is therefore not always reflected in these types of documents. Wartime correspondence differs clearly from 'normal' peacetime letters . In the case of military mailing service, transport times between 6 and 30 days can be assumed, provided that the shipment was not prevented at all due to an interruption of the postal service or loss. The conversation cannot take place immediately, but rather be "simulated in thought" by the writer, and more often than with correspondence in normal times, the transport route itself, the account of sending and receiving, will be the subject of the exchange. The time delay has an effect, especially in war with its rapid changes; a message can be out of date before it reaches the recipient. The awareness of this will influence the content of the letters. Nevertheless, the postal service provided a communication tool to stabilize personal relationships and to share news, emotions and experiences.

These documents play a crucial part in research into individuals and their personal stories, although there are also limits to this analysis. Censors banned soldiers from revealing their position or giving details about combatants or units in case the documents were intercepted by the enemy. Next to official army regulations, the soldiers concealed certain facts or traumatic events either to avoid causing worry for their loved ones or because of the inability to express the horrors and the deaths they had to endure in battle.

Letters offer a filtered and curated impression of the war experience but are nevertheless valuable for research about individual stories.

Letters by Luxembourgers - Between homesickness and the wish for cigarettes

Luxembourger conscripts were torn apart from their families during their labour and army service; they were torn away from their friends and social environment. Letters promised a means of communication.

The content, as well as the quantity, depended on the person who wrote, where he or she was stationed and to whom the letter was addressed. But every letter sender had one thing in common: even at the front in Russia or in the labour camp in Bohemia the young recruits remained sons and daughters, brothers and sisters. They shared their fears, their hopes for a speedy war’s end or they wrote simply about daily events (marching, sleeping, details about food) and their wishes and needs to receive warm clothes, groceries and cigarettes. Besides the prohibition of writing in other languages than German, many letters were held in Luxembourgish. The recruits expressed their personal thoughts and their desire to desert in order to escape as soon as possible this ludicrous situation of fighting in German uniform (despite the fact that mentioning desertion could have ended with severe consequences such as execution).

The young men for instance, talked about contacts with locals in Russia and in Poland, fighting against the resistance (partisans), longing for intimacy with women, or friendship, and the postponing of hopes and wishes and future plans. Nevertheless, the letters provided the opportunity to share thoughts and memories of better times, hopes and future plans and asking about the state of things in the Hemecht (home). Next to the situation at the front or in labour service camps abroad, those who stayed at home experienced difficult and frightening situations as well, such as intimidation by the National Socialist occupation authorities, air raids, food shortages and in general the feeling of uncertainty as to how the war would continue.

Letter circles and pen-pal networks were established to write the recruits so they could maintain their links to home and not be forgotten. Young women wrote regularly to their fellow Luxembourgers in many parts of Europe to provide them with the daily news or to send writing material and cigarettes. For the men called to arms, this meant comfort and support, even a word like “Hello” from the distant homeland.

The two spaces, home and front, have to be taken into consideration to study the individual experiences and biographies of the generation who were born between 1920-1927 and their families.

Behind every letter lies another story, behind every story another fate.

Call for contributions

To extend the collection and to profit from these unique sources more documents are needed to conduct further research.

Therefore a Call for Contributions from the public is carried out by the WARLUX team. Families and witnesses in Luxembourg are called on to share their memories and personal documents. WARLUX intends to find and identify personal documents, diaries, memories and photos which provide insight into individual experiences and stories during World War II. Families and witnesses are asked to look in their cellars and attics, in old boxes and cupboards from grandparents and parents to find documents and photographs about this period of time.

The research team at the University of Luxembourg will (according to the agreement of the donors) scan it and store the documents properly. The families could send the documents to the University, or the researchers collect them themselves (in compliance with the hygiene measures). After digitising the documents (with the approval of the families), the team brings the originals back.

The letters and other ego-documents will be used for qualitative data analysis to add to our archive and to study the individual experiences of the researched generation.

To contribute and support the research of WARLUX

please contact the team via email, telephone or fax :

E-Mail: warlux@uni.lu

Telephone + 352 46 66 44 9575

Fax: +352 46 66 44 36702

Further reading

- Martin Humburg, Das Gesicht des Krieges. Feldpostbriefe von Wehrmachtssoldaten aus der Sowjetunion 1941-1944, Opladen; Wiesbaden 1998.

- Klaus Latzel, Kriegsbriefe und Kriegserfahrung: Wie können Feldpostbriefe zur erfahrungsgeschichtlichen Quelle werden?, in: Werkstatt Geschichte (22) 1999, p. 7–23.

- Nico Everling, Liebe Jett. Feldpost eines Luxemburger Zwangsrekrutierten, Luxembourg 2003.

- Katja Rausch, „Es geht alles vorüber, es geht alles vorbei...“ Philippe Gonners Briefe von der Ostfront 1942-1944, Luxembourg 2003.

- Veit Didczuneiet, Jens Ebert and Thomas Jander, Schreiben im Krieg. Schreiben vom Krieg. Feldpost im Zeitalter der Weltkriege, Essen 2011.

Find more about the research and about “Warlux”

on the blog Digital War History: https://digiwarhist.hypotheses.org

Twitter: https://twitter.com/warlux_c2dh

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/warlux_c2dh/