One night in 1906 in the Grund of Luxembourg City, under the curved Bridge Adolphe, strollers made a terrible discovery: the body of a young man was found, without a head and badly battered. What starts like a thriller novel, is, in fact, true. This unknown episode in Luxembourgish history can be found in the files of the "cour d'assise", held by the National Archives of the Grand-Duchy.1

The analysis and inventorization of these court records from 1900 until 1940 at the National Archives was part of the research project "HistJust" (Histoire de la Justice). The aim was to identify and to collect relevant documents for the ongoing research about law and order from 1815 until today. The court files mark only a small period of the work of legal institutions, but offers a unique contribution to further research in the field of history of justice.

- 1. ANLux CT1157 Mathias F., Nicolas W., Théodore G., Michel F., Antoine T., Jean S., Josephe G. , Nicolas G., Guillaume S., Marie B., Jules F. - Accusés de meurtre / Suspectés de meurtre (1906-1930).

The documents from the Luxembourgish justice authorities, especially from the "cour d'assise", tell stories about blood and thunder, murder and thieves, but also reveal stories about people, their personal histories, and their struggles in everyday life. The records beat witness to the hopes and dreams of ordinary people living in the first half of the 20th century in the Grand Duchy.

The "cour d'assise" was established in 1810 as part of the French “Département des Forêts”. It was called into duty only for severe criminal cases, such as personal injury, rape, murder or theft. The judges of this court were appointed from 1831 on by the Supreme Court only for specific trials, which were held in the old Palace of Justice in the Rue Palais de Justice in the upper city of the Luxembourgish capital. The cases of the "cour d'assise" are well documented; the records from 1810 until 1940 are already inventoried, and are/will be accessible for further research.1

These historical documents cover the efforts of juridical authorities and include the detailed procedure from the police investigations, the indictment until the trial and the decision by the judges. The daily business of police, state attorney, defenders, judges and testimonies of the convicts highlight the functioning of the legal system and the application of the law in Luxembourg.

- 1. For questions about accessibility and research, please consult the Archives Nationales de Luxembourg - https://anlux.public.lu/fr.html, archives.nationales@an.etat.lu.

After the discovery of the headless corpse in the Grund, the authorities launched an investigation. The possibilities and the investigation tools at that time were limited. The police ordered an autopsy for the body. But because the man did not have any documents on him and DNA-tests had not yet been invented, he remained unknown. Nobody seemed to miss him. Public announcements and messages were published in the newspapers; police and the prosecutors interrogated witnesses in the area of the Grund, the Petruss Valley, Hollerich and the train station area. The district was very disreputable during that time. Police assumed the victim might have visited prostitutes there and ‘sinned’. Investigations were held – without any results. The body remained unidentified throughout the entire investigation; some suspects were arrested, but soon rereleased. The headless corpse remained unknown so far. The police gave the victim the name Jean Pommerelle.

The documentation of the efforts of courts and police are preserved in the storages of the Nationale Archives at the Plateau of St. Esprit. The case of Jean Pommerelle includes two big archival boxes of records. Like the story of the murder of Pommerelle, other stories are waiting to be told. Stories about the abyss of the human soul, about the darkest chapter in Luxembourg's history. Stories about quarrel, beatings, alcoholism, lost and forgotten individuals in the shady corners of the labourer districts and Gare quarter of the capital.

Women in trials

In the majority, more men were convicted of murder than women. However, women are represented in the documentation series of the "cour d'assise" not only as victims but also as suspects and convicts. They were sentenced for infanticide or for murdering their husbands or lovers. Nevertheless, infanticide remained the main accusation against women at the court. Over the decades, the cases repeat themselves: unmarried young girls, became unintentionally pregnant and killed (alone or with the help of others) the new-born shortly after the birth. The record contains cases of convicted women such as of Susanne, Elise and Catherine,1 whom the judges brought into trial and punished by sending them to jail. The police reports contain personal and very intimate details about these girls and women; their way of life was investigated, who they loved, how they suffered. In case of a love affair outside the marriage, the woman was suspected of seducing the man and her becoming pregnant was perceived as her own fault. Being in this situation as a young girl, unmarried and uneducated or unemployed, the women did not see any chances in raising a child alone. They were dependent on men or their families, but they were expulsed or feared social exclusion. During the first half of the 20th Century Luxembourg was a strictly catholic and conservative country. Illegitimate children and sexual intercourse before or outside the marriage were deemed inappropriate. The concerned women feared the consequences of pregnancy or having a child alone, feared the disapproval of their own family, local society and the church and resorted the last desperate measure in killing the new-born. Abortion during this period was definitely illegal, even if the mother was in danger or the child was considered disabled, the termination of pregnancy was severely punished. A person (a doctor or midwife) who had performed the abortion could also have been convicted.

The stories of Susanne, Elise or Catherine do not differ significantly from each other. All women belonged to the working class and became pregnant through a love affair or even through rape. For economic reasons and social reasons, they killed their new-borns. The act is punishable under the Code Pénal and was negotiated by the "cour d'assise". Despite the severe accusations (including murder), the young women were given a maximum of five years of prison as punishment.

In studying the judges' decision over the decades, a researcher can observe various trends and developments in society and their interpretation of the law: abortion, for example, is no longer punishable (until the 12. week)2 and the death penalty and forced labour have become final abolished. Women and men continue to be brought to justice and are punished by our current ethical and social understanding of law and order.

The court cases are a well-documented collection of evidence by the police. In addition to reports, testimonies and interviews, the files show initial attempts to use forensic methods like fingerprints or microscopic analyzes as well as medical and psychological reports. In this way, new evidence was used during the legal proceedings and the conviction of the suspects.

Modern Police Work

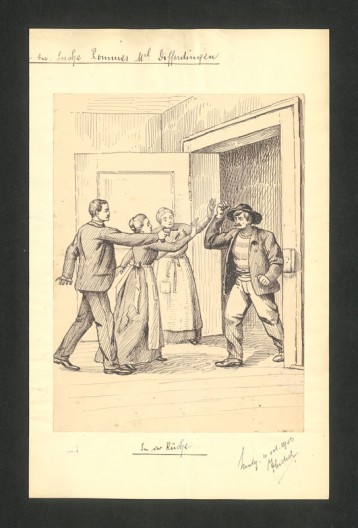

In the early 20th century, photography was not yet widespread, therefore the documentation of the crime was sketched, documented and written down. The sketch of a crime replicates the details and the sequence of the act. In 1903 attempted murder was captured precisely in drawings in order to reconstruct the crime scene and to use them during the trial (see image "Victim at the crime scene"). This case refers to attempted murder after an argument about a stolen cabbage, and the responsible one was sentenced to 5 years in prison. The sketch supported the reconstruction of the crime for police, prosecution office and the court.3

- 1. ANLux CT1133 Susanne J. - Accusée d'infanticide (1904) ; CT1102 Elise B. - Accusé d'infanticide (1901) ; CT1395 Catherine S. - Accusée d'infanticide (1926-1958).

- 2. Loi du 17 décembre 2014 portant modification 1) du Code pénal et 2) de la loi du 15 novembre 1978 relative à l'information sexuelle, à la prévention de l'avortement clandestin et à la réglementation de l'interruption volontaire de grossesse. (Mémorial A n° 238 de 2014).

- 3. ANLux CT CT1112 Jean Joseph Z. - Accusé de tentative de meurtre (1909).

Other methods of proving and documenting crime arose at the beginning of the 20th century, such as fingerprints, x-rays, detailed autopsy reports, the occurrence of ballistics report and photographs.

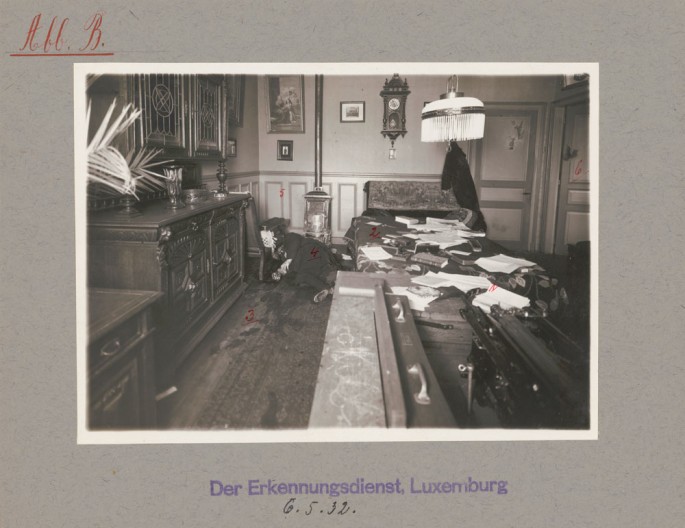

The new methods brought light to the procedure in Court, justice and police work. An example for these advances can be found within a story of robbery and murder: In April 1932 two men broke into an office to steal money in Limpertsberg. They killed a man and disappeared. The police were called and began their investigations. They took pictures of the crime scene (see image 2) and investigated the room for other traces such as the fingerprints (see image "Fingerprints from the crime scence").1

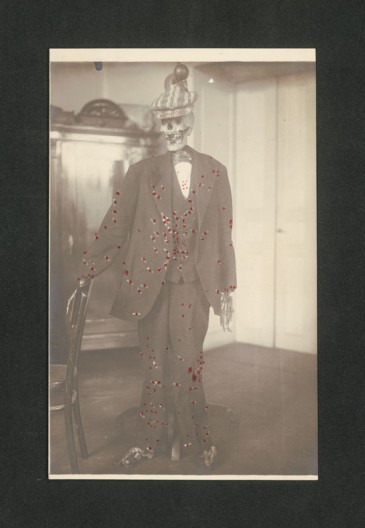

The second man denied any participation in the killing and told the police he was innocent. The police investigated the clothes of the offenders for any possible traces. The clothes of the man who pleaded not guilty were also checked for bloodstains. The officers put the suspects’ clothes over a skeleton in order to re-enact how the victim died and where the blood splashes had come from (see next image). Bloodstains on the clothes of the second suspect were found as well and proved that both men were involved in the crime (the murder). This story is just a short version of the thick court file but demonstrates pretty well the value of the storyline itself.

- 1. ANLux CT1435 Jovo M.; Georges C. - Accusés de vol et de meurtre (1932-1942)

This whole source corpus promises new and unknown insights. The police reports document precisely the social life of victims, suspects and offenders, gives insights into the work of the legal authorities and offer a unique perspective on Luxembourgish history and the history of justice.

By the way, the real identity of Pommerelle was never been solved and his murderer remained unknown.

I want to thank the staff* of the National Archives very much for their support and understanding and for endlessly delivering and scanning files and patiently answering the many questions that I had.

Villmools Merci!

*Especially Faris Pacariz, Patricia Lambert, Philippe Nilles and Corinne Schroeder!