From a cultural perspective, the city of Milan in Italy has a lot of activities and places to offer. Milan was not only designated by the Unesco as creative city for literature, but also chosen for hosting the European Culture Forum (ECF) from 7 to 8 December 2017. It was the first time that it was held outside of Brussels. The neighbourhood in which the event took place was quite fitting: opposite of the venue was an old factory building repurposed for creative industries with offices and spaces for cultural activities and adjacent to the Museo delle Culture.

The ECF 2017 marked the official launch of the European Year of Cultural Heritage 2018 (EYCH), though for budgetary reasons and according to the EU decision taken in May 2017, it only starts on 1 January 2018. I hoped to learn more about cultural policies in the EU and was particularly interested in the topics raised. In the end, however, and except for some interventions, the ECF was rather an event for uncritically celebrating Europen culture and values.

The European Year of Cultural Heritage 2018

The EYCH is not the first such year – there have been others, for instance the European Year of Creativity and Innovation in 2009 and the European Year of Intercultural Dialogue in 2008. One could ask whether these years succeeded in leaving a lasting legacy and how much they raised the awareness of European citizens. In one panel, a participant voiced exactly this issue and asked the public whether they remember the last European year (not many seemed to know). During the event, some references were made to the European Year of Architectural Heritage 1975, which was an initiative by the Council of Europe. According to Miles Glendinning, this year did not have a lasting impact and turned out to be more ephemeral than the Unesco heritage policy (Glendinning 2017). However, at least in Luxembourg, it had a certain impact on the cultural policy, as the protection of heritage was extended from isolated buildings and monuments to sites and whole city quarters.

The initial idea for the EYCH went further back than the official EU decision in May 2017 – which also left little time to the member states to prepare for 2018. Indeed, as Uwe Koch, German national coordinator of the EYCH, explained, the discussion started in 2013/14 in the German cultural heritage committee. In 2015, a draft for a European Year was presented in Berlin and handed over to the European Commission. This draft stressed the importance of identification with cultural heritage, participation, cross-border cooperation and heritage as a resource for the future. Thus, the EYCH was not an idea of the European Commission. The welcome addresses, however, did not mention this fact. Sneska Quaedvlieg-Mihailovic, Secretary General of Europa Nostra, was one of the rare people who highlighted the important work of the civil society in making this possible and putting it on the agenda of the policymakers.

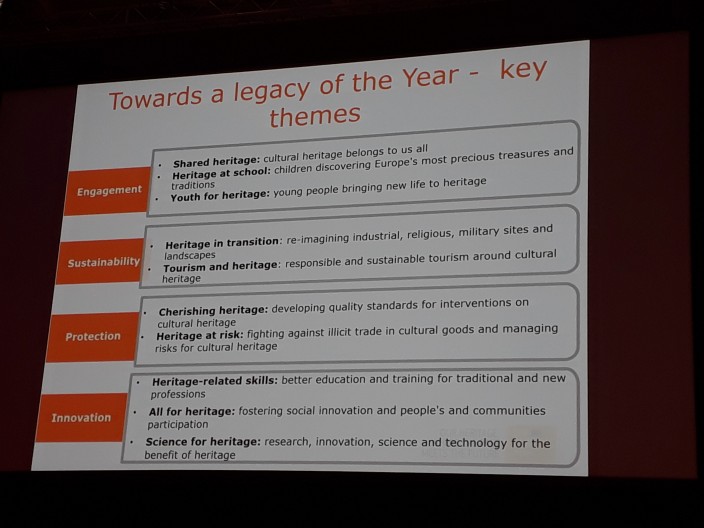

According to the EU decision, cultural heritage is an important factor for intercultural dialogue, cultural diversity, quality of life and economy. The official objectives of the EYCH consist in creating a stronger link between citizens and the shared common European heritage. The latter plays an important role in supporting the cultural and creative sectors. Ten European initiatives have been defined, regrouped in four pillars: engagement, sustainability, protection and innovation. It is worth pointing out that cultural heritage is not only something of the past, but connected to the future, and that innovation and creativity play a key role. Cultural heritage, thus, is not considered to be something rigid. Quaedvlieg-Mihailovic was pleased that “the narrative has changed” and that heritage is now as much connected to the past as to the future.

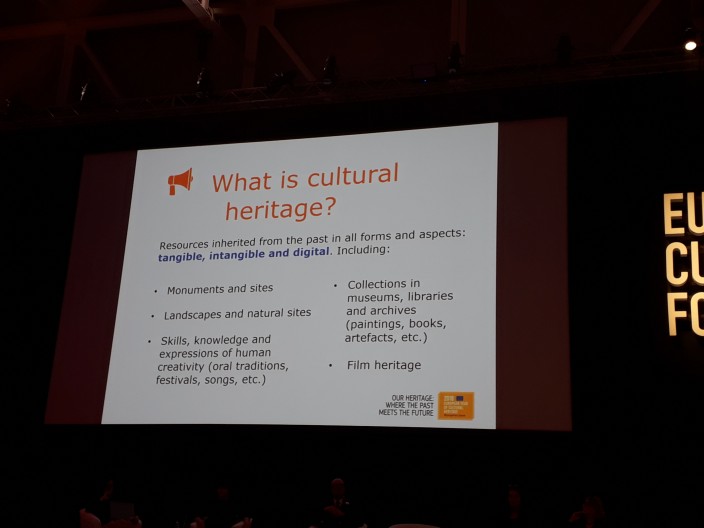

The EU definition of cultural heritage is a very vast one, including tangible, intangible and digital heritage, from monuments and sites over expressions of human creativity to museum collections and film heritage. This definition combines traditional forms of heritage with anthropologic aspects as promoted by the Unesco. The new dimension added is certainly the digital one. Among the welcome speeches, it was the Estonian Minister of Culture, Indrek Saar, who focused on digital technologies and raised some challenges of digitization of culture and digital access. He stressed that easy access is not the same than equal participation. Jill Cousins, Executive Director at Europeana, mentioned the leading role of the EU in the digitization process. For Johannes Ebert, Secretary General at the Goethe Institut, “digitalization” can help in reaching more and younger people. However, the digital did not always appear as something positive. In EP President Antonio Tajani’s speech, the digital era was depicted rather as a challenge than as an opportunity: “We have the duty to defend our heritage, even in the digital era”. Speaking from a different perspective, Michael Walling (artistic director for Border Crossings) argued that we need spaces where people meet physically, not virtually, in order to recognise the common humanity.

The year is founded on a governance approach, which means cooperating with as many actors as possible and including them in the policy process. Though there is a European campaign with an own label, slogan (“Our heritage: where the past meets the future”) and hashtag (#EuropeForCulture), the event is decentralized. The member states can allocate an own budget for the year and design their own campaign (tellingly, the UK has no budget for the EYCH). Luxembourg (#HeritageforFuture) and Germany (#SharingHeritage), for instance, have their own hashtags. The EU budget for the Year amounts to 8 000 000 EUR, of which 3 000 000 EUR originate from the budget already allocated to the Creative Europe programme.

Discourses between identity and economic rationales

The question of identity was regularly raised during the forum, especially as identification with common European values is a strong concern of EU policymakers. Indeed, the EU pays much attention to promote a common European identity, through the European hymn or the European flag, for instance. Cultural heritage is another dimension of these policies. How this common European heritage looks like remains unclear – and there does not seem to exist a clear opinion, even at EU level, which tries to bridge the gap between national heritage and European values. For Tibor Navracsics, European Commissioner for Culture, culture and cultural heritage “belong to the most vivid expression of the European common identity.” Antonio Tajani probably presented the least vague vision of a common cultural heritage – and simultaneously the most exclusive one. He attributed a very high importance to the Christian heritage (“not a religious, but a cultural issue”, as he noted). What struck me most was his allusion to the fight against the Persians when he argued that liberty unites all of Europe and that freedom is the most important heritage. It would certainly have been difficult to invent an even more time-spanning continuity. Tajani also warned that if “we” do not defend “our” identity, it would cause serious moral and economic damage. “The stronger our identity”, he declared, “the easier for us to be understood”. One can certainly question whether this view on identity is not one of rigidness, of an inwards-looking perspective (self-centered, understanding oneself) as opposed to an outwards-looking viewpoint (openness, understanding the “other”). Many panellists avoided discussing in detail the question of identity. In one session, however, the concept of “multi-layered” identity came up, defending the idea that we have multiple identities, such as local, national and European. Though I haven’t read enough about identity (especially from a social sciences viewpoint), it is probably the one concept used during the forum that comes closest to an accurate description of who people are.

One focus of the European Union is the support of the creative industries, a concept that has been increasingly used since the 1990s, promoted at a national level by countries such as Australia and the United Kingdom. Though the creative industries do not overlap with the cultural industries (the latter are much more linked to mass production), both have been used at the ECF quite interchangeably. Creativity was a predominant idea in the speeches and at every spatial level. A reason might be its convenience for policymakers and the possibility to easily reach a large support because of its ambiguity. The researcher Dave O’Brien has already noted that it “is hard to be against” and “a difficult idea to reject” (O’Brien 2014, 6). The EU, too, has included the creative industries in its policies, as shown by the programme Creative Europe, but also by Horizon 2020 for innovation and research. Both programmes, and especially the first one, are involved in the EYCH. Additionally, the speakers and panelists regularly invoked the economic and touristic value of culture and the importance of the creative industries for job creation. Only on some occasions did the societal dimension of culture emerge in the discussions, when Quaedvlieg-Mihailovic described culture as an “antidote to populism”. Or when Petra Kammerevert, chair of the EP committee on culture and education, pleaded for bringing together culture and education (rather unsurprisingly considering the committee she is presiding) and reminded that culture and cultural heritage cannot be reduced to a material dimension. The strongest advocate against the use of culture for simple economic reasons, or as a tool in general, was Michael Walling (artistic director of Border Crossings). He called for culture to be put in the middle of politics, and marginalized people in the middle of culture. Culture, according to Walling, should not be instrumentalised for economic growth, or imposed as a tool.

Banal (supra)nationalism?

Cultural policy can have different spatial dimensions, as illustrated, for instance, by the researchers David Bell and Kate Oakley. The European Culture Forum, rather unintentionally, revealed at how many levels cultural policy is present: from cities over regions and countries to the supranational. I had the impression that the Forum programme wanted to give justice to all of them, which resulted in a rather absurd amount of welcome and opening speeches.1 However, the simultaneous existence of local up to supranational authorities can pose a challenge to governance and coordination. Questions related to this issue inevitably came up, though there were never clear answers given and none from the policymakers. Indeed, differences between the EU campaign and the national campaigns exist, though no contradictions. The EU wants the EYCH to be decentralised. The money allocated is far from being sufficient, which is the reason why the member states can also decide on a budget for their national campaigns. These campaigns remain within the framework defined by the EU, but can stress different aspects: in Germany, heritage as something to be shared, in Luxembourg, heritage as a resource for the future. But what about cities and regions? How are they part of all this? Does the multiplication of authorities also lead to tensions and competition? These questions also include reflections on bottom-up and top-down approaches. A general consensus existed at the ECF on including people in the process and in cultural heritage, for instance through storytelling.

The politicians, who were very keen on highlighting the importance of culture in their area of responsibility, did not actively participate in the various sessions. Among all the panellists, I counted only two active politicians. In the plenary session on “Challenges (for culture) in Europe: 2007, 2017, 2027”, there was one former national politician, and none from the EU. In the following Q&A with the public, some spectators raised important questions on financial issues, on the coordination between different administrative levels, on whether culture is free and independent or an instrument. Politicians and cultural policymakers in office at the moment should have been in the panel to answer them. But they weren't.

- 1. It is certainly worth to list them here as an illustration: the mayor of Milan; the councilor for culture of Milan; the President of the Lombardy region; the councilor for culture of the Lombardy region; the Italian Minister for Cultural Heritage and Activities and Tourism; the chair and vice-chair of the EP culture committee; the European Commissioner for Education, Culture, Youth and Sport; the Minister of Culture of Estonia (in the context of the Estonian EU presidency); and the President of the European Parliament. One could also add to this list the short video message by the President of the European Commission.

The European Culture Forum was barely a place of critical discussions. This does not mean that the ECF was uninformative. There were also interesting projects presented. One that impressed me very much is located in Athens. The BIOS Romantso is a creative hub in a poor and neglected neighbourhood of Greece's capital city, where children don't go to school, where many unemployed people and migrants without clear perspectives have to struggle on each day. Despite all of this, the hub has been able to attract young people working in a formerly derelict building and interacting with the immigrants of the area. New shops have been opened up, street events are organised, and basketball courts have been created on the terraces of the buildings. It is certainly a good illustration of what culture can do to a neighbourhood and to society.

Yet, debates on the financial, administrative and other challenges were completely missing. The projects shown at the ECF were successful ones, but I suppose even they had to deal with problems. If a person from the public would not have asked how the BIOS was funded, no one would have known (it was funded, by the way, by not paying taxes to the state and using that money for investing in the creative hub). What about the projects that failed? It is important to exchange best practices, but it is as much of relevance to learn from mistakes. In another panel, six young and committed people told their stories about cultural heritage and what they learned from it through their activities. But what about those young people in Europe and around the world who are too poor to travel and profit from these opportunities, from cultural heritage, from getting in touch with their peers?

There were some intersting discussions. Nevertheless, it was mainly an event where European culture (whatever it is) was, from the official side, uncritically celebrated. I was wondering whether one could not use Michael Billig’s concept of “banal nationalism” and apply it to the European level (banal supranationalism?). Billig used this concept to describe the ways a nation is represented and rebranded through the use of symbols, images, and other forms of representation to elicit a sense of belonging to the nation (it could be combined with Benedict Anderson’s “imagined communities”). As Billig explained, “in the established nations, there is a continual ‘flagging’, or reminding, of nationhood” (Billig 1995, 8). The EU uses the same dispositif as nation-states to create a sense of belonging to common values. And is one of the objectives of the EYCH not exactly that?

I could not stop but comparing the ECF to the Kulturpolitischer Bundeskongress I attended last June and conclude that the latter had much more critical debates. It is also worth to point out that the Bundeskongress had a whole panel dedicated to the EU foreign cultural policy. At the ECF, it was barely mentioned, at least in the plenary sessions and the parallel workshops I attended. And within the framework of the EYCH, the only foreign policy aspect is the possibility for associated non-EU countries to participate. When reflecting on the ECF as a whole, I am not sure if it helped me to stay more informed on the EU cultural policy. It was certainly revealing of existing tensions and ambiguities in discourses on culture and cultural heritage, only confirming what I was already suspecting or at least read in academic literature. I will certainly follow the EYCH with much interest and take advantage of some of the events taking place in its framework. The question remains if it will have a lasting legacy: at least, it is one of the big objectives defined by the EU.