I met Sandra Gaudenzi at the IF Lab workshop in 2018 for my web documentary project. As the only IF Lab participant with an academic project, I could truly benefit from the magic of working in an amazingly creative setting surrounded by professionals with different backgrounds. Since this interdisciplinary and user-oriented approach fits into the thinkering spirit and general scope of our centre, Sandra and I decided to organise an experimental workshop targeted at professional historians. A real IF Lab experience of 10 intensive days working on specific projects was of course not possible. The aim instead was to experiment with the potential of introducing interactive storytelling into our academic practice as historians and doing so by developing and prototyping an interactive story together in groups.

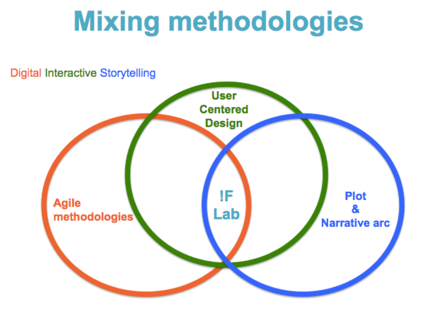

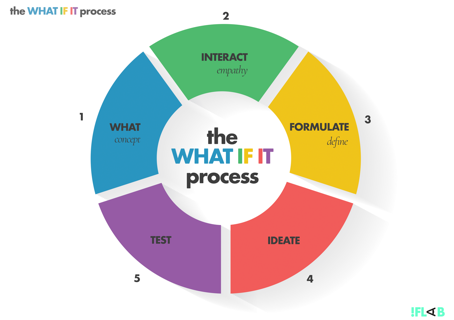

The workshop started on the Tuesday afternoon. Sandra Gaudenzi began with an introduction to the different genres of interactive storytelling and discussed the ways it could enhance our practice as scholars. She referred to Benjamin Hoguet’s definition of interactive storytelling as “the art of telling stories enhanced with technological, social or collaborative interactive features to offer content adapted to new behaviours in a rapidly changing cultural ecosystem”. (Hoguet, 2014) Sandra then introduced the participants to the IF Lab methodology, which seeks to find an effective mix of Design Thinking, Agile methodologies and storytelling. This user-centred methodology is called the WHAT IF IT process (1. What concept > 2. Interact > 3. Formulate > 4. Ideate > 5. Test). The added value of this approach is the constant feedback that allows us to readapt the project to the user during the creation process. The two days were an opportunity for historians to test this approach playfully in groups and see if it could be applied to their own projects.

The participants were asked to imagine an app, an interactive experience on mobile, social media, web, VR or AR that can explain the current explosion of populism and immigration tensions in Europe to a chosen target audience. We agreed on this very general topic from which each team would develop a different interactive story according to its interests.

The participants formed three groups of 4 to 5 people, selected a case study related to the general theme and filled in the Concept Canvas. This exercise involved briefly formulating WHAT the story is about, WHY it is relevant, WHO the target audience is, WHAT impact it will have on the audience and WHY it should be interactive.

The IF Lab methodology suggests starting with the user, rather than with the story. Identifying the target group for our project first requires empathising with the user. The second exercise was then to build a persona, not only defining who he/she is but also concentrating on his/her needs, frustrations and insights as well as his/her natural and virtual environment. The participants filled out the Persona Canvas based on a role play, where one member had to interview the persona and take notes. Storytellers need to be aware of the impact they intend to have on an audience. The participants were therefore asked to fill in the User’s Impact Canvas, writing down what the audience should know, feel and/or do after the user experience.

We then began the ideation process with a short group brainstorm in which all the members wrote down on a large sheet of paper any possible solutions they could think of for the persona through their story and had to come up with one idea to prototype during the workshop. Based on the idea they had selected as a group, they were asked to individually think of a platform that would best meet their expectations and develop the main content.

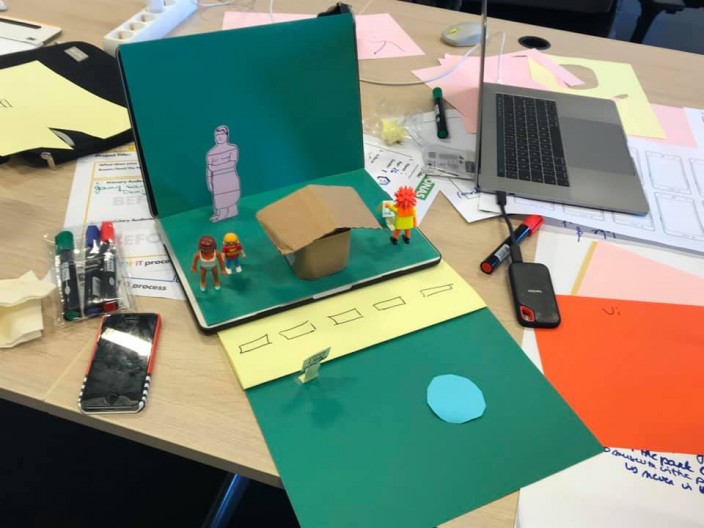

On the second day, the teams decided on a platform and started the paper prototyping process. This exercise included drawing a walk-through of the user experience and visualising the user’s interaction with the interface and the content. The teams had an entire morning to prototype their project idea. The storyboard could either be on paper or digital, and even Lego prototyping was allowed! Literally no restrictions were placed on this creative process.

In the afternoon, Sandra Gaudenzi gave a Hands-on lecture entitled “Why use interactive digital storytelling in academia?”. The lecture was aimed at the C²DH team and we had the honour of welcoming a number of practitioners from the creative industries. Sandra Gaudenzi took the audience on a journey through different history-based interfactuals, a term she coined to represent any project that intends to document the real, and that does so by using digital interactive technology (Gaudenzi, 2013). Interfactuals not only have the potential for scholars to explore alternative forms of divulgation of scientific knowledge in the digital age, but also offer the opportunity to think through digital media. Interactive digital storytelling evolves our research practice and raises questions of agency when the creation process involves the audience.

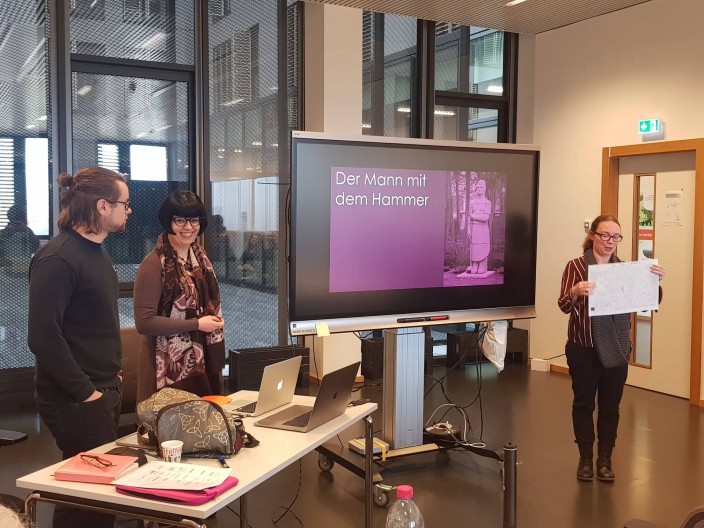

At the end of the workshop, each team pitched its interactive story and presented the prototype they had been working on. This was an opportunity to fictionally test the user experience, the real testing being ideally undertaken with the real target audience. All the groups presented very engaging and original results. Interestingly, each prototype turned out to address completely different audiences, tackle different issues and explore a different platform. It was truly impressive to see the remarkable results, considering that each team basically had one morning to prototype its interactive story.

The first team decided to challenge potential young but uninterested voters for the upcoming EU elections and convince them not to waste their vote. Based on the digital environment of the target group, the way into their project was a series of funny GIFs on social media that would catch users’ attention and take them to an interactive website with several challenging questions about the consequences of letting others vote in their place.

The second team tailored its interactive story to 10 to 12-year-old children, frustrated because they did not understand the rise of right-wing movements (e.g. the right-wing radicalism in Chemnitz) they were constantly exposed to in the media. The group’s goal was to help those children find answers that their parents and other adults they came into contact with were not providing. The participants created a fictional character called Newspepper, a robot from Saturn, who came to planet Earth as a journalist. Users were invited to assist Newspepper with its research, resulting in an article including a selection of pictures with matching captions. During their pitch, they presented an animated stop-motion prototype of the user experience.

The third team reflected on the perception and fruition of controversial monuments, employing as a case study a statue in Dudelange. De Mann mam Hummer, sculpted by a Nazi sympathizer called Albert Kratzenberg, had progressively lost its initial connotations acquiring different layers of meaning. The group’s target audience was the local population and local members of the socialist party who have been using this monument as a meeting point for their rallies. When walking through the city, the target audience encounters different signs with a QR code and is invited to play. This QR code or a link on social media leads users to a web page, where they see the monument break into pieces and must fix it by playing a game. The game involves finding the right answer to different questions based on the monument, for instance its sculptor or the historical context. Users watch videos of members of the local community answering the questions and select the correct answer. For each correct answer, they earn one piece of the monument. This participatory project is an effective way of playfully connecting users with historical monuments.

Ultimately, those two days of experimenting with the use of interactive digital storytelling revealed the relevance of applying a user-oriented approach whilst developing an engaging and/or participatory public history project. In practice, a user-oriented approach is essential for any project embracing interactive storytelling. Furthermore, the workshop demonstrated that involving non-historians and team members with considerable (audio-)visual and technological expertise generated a strikingly beneficial synergy during the prototyping process and the general development of the project.